This is the first of a series of essays on capitalism. This, the first, is a very theoretical discussion, one relatively light on examples. However those that follow will have examples aplenty. But the theoretical framework is needed to make to gain what I argue is a deeper understanding and productive sense of them.

Americans’ understanding of the complex issues confronting us today is handicapped by confusions over four terms essential to their comprehension. The two most seriously confused are the “market” and “capitalism”. “Democracy” and the “state” follow close behind. Confusion over them makes coherent analysis of many important issues impossible.

Understanding a fifth term, “civil society” enables us to get a much clearer grasp of how all five fit together.

What is civil society?

The most succinct definition of civil society I know of is by David Hardwick: the “interdependence of independent equals.” From this brief term the rest emerges. Civil society is defined by equality of legal status. Each member is free to enter into any peaceful cooperation they wish, so long as it is consensual and does not aggress against another. It is a defining feature of modern liberal civilization. Among the many threads in our history is the slow extension of equal status from White men to include White women, Blacks, Indians, and Asians. Civil society also grows in depth, as forms of peaceful cooperation once banned are made matters of personal choice. Marriage was once voluntary so long as potential spouses were of the same ‘race’. Civil society deepened when that limitation was removed. The same is happening today among GLBT Americans. Especially for those who are not White heterosexual males, there is room for improving equality of status, but what already exists is significant.

To the extent people are free to interact as equals, networks of cooperation grow in extent and intricacy linking more people over more diverse issues and utilizing more information than could ever be deliberately managed. Alexis de Tocqueville, the first careful observer of American civil society wrote:

In no country in the world has the principle of association been more successfully used, or more unsparingly applied to a multitude of different objects, than in America. Besides the permanent associations which are established by law under the name of townships, cities, and counties, a vast number of others are formed and maintained by the agency of private individuals.

Think of the World Wide Web as a kind of mirror of civil society’s connections, reflected in pixels, except that civil society is far more complex. The most inclusive civil society is what Hayek called the “Great or Open Society.” (1976, 12)

Civil society is best conceived as a continually changing pattern, rather than an end state. It is far more verb than noun, continually forming and reforming itself through the networks of cooperation it fosters. In its most inclusive sense some places within the network will have many nodes and many links, others will have fewer. In totalitarian states such as North Korea there will be few if any.

When civil society is strong it makes peace, freedom, and prosperity possible for more people than any other social form. But its successes generate forces with a stake in limiting and weakening it. Our confused vocabulary leads us astray when trying to understand them.

Democracy

Civil society is not a libertarian anarchy. At any level the cooperation it facilitates takes place within a framework of procedural rules, modified and shaped by values deemed necessary to protect and serve its members as a whole. In civil society these more specific rules do not undermine the equality of status that makes for full membership. The universal abstract procedural rules of freedom of speech, contract and property rights are modified and shaped by more specific rules such as those covering issues of slander, pollution, speed limits and the like. (For example, in the US trespass rules are vastly stricter than in England or Norway, but all honor private property rights in land. The US and France have laws against slander, but Paris can sue FOX News over its lies in ways Americans cannot.) These distinctions give privileges to none because they apply equally to all. They simply shape the contents of the bundle of rights we describe as “owning land” or “freedom of speech.”

These differences influence the patterns of cooperation arising between members within different civil societies. Consequently civil society will be different in different cultures even though in all of them each participant’s formal status is equal and all have complex networks of voluntary cooperation.

These rules elaborating on basic principles must be made and will be made differently in different places. Because those who make rules will tend to weigh their own interests more heavily than the interests of others, they will take advantage of any undemocratic process to undermine civil society whenever it is advantageous for them to do so. Therefore, while civil society can arise in many different political systems, democracy of some sort is the one most in keeping with its principles, and safest for them to be protected. Everyone must have equal status at some significant point in the rule-making process. In large societies this means having fair elections.

I shall return to the issue of democracy below. But I hope it is clear it is the only political system in principle able to respect the principles of civil society while making the rules required for it to exist.

Spontaneous orders

There are two kinds of order in society. The one best understood is some kind of instrumental organization designed to pursue particular goals in some order of importance. Businesses, bureaucracies, clubs, sports teams, and universities are examples. Less recognized are orders that arise without deliberate intent through people following rules that facilitate cooperation and generate standard forms of feedback simplifying what participants need to know in order to act effectively. The most basic such order is language where most speakers are not even consciously aware of the rules they follow while effortlessly communicating with other speakers of the same language.

Civil society is particularly hospitable to the rise of more specialized versions of these kinds of order. F. A. Hayek while studying the market and Michael Polanyi while studying science called them and orders like them as “spontaneous orders.” They contrasted them to instrumental organizations. (Hayek, 1973; Polanyi, 1969)

Unlike organized hierarchies of authority, spontaneous orders emerge from everyone following the same rules, but for independently determined purposes. As they develop, some of the networks arising within civil society develop standardized feedback signals enabling greater coordination between participants than could ever arise from deliberate ordering.

An organization has a set of reasonably clear goals and any discovery needed for an organization is how better to attain those goals. However in a spontaneous order people pursue self-chosen goals some of which will conflict with others’ similarly chosen goals. Spontaneous orders are, as Hayek put it, a “discovery process” where all participants contribute to feedback signals assisting them in making their decisions better than they could within any alternative framework. Success is guaranteed to no one. As in a game, success arises from the competition between different plans, often of unknown compatibility, pursued within a procedural framework applying equally to all.

Ludwig von Mises and Hayek first appreciated the importance of this feedback when critiquing arguments for government control of the economy.(Mises, 2011; Hayek, 1948) They argued socialism in this sense could never work because there was no real alternative to the market price system for efficiently allocating resources to competing uses. The market process could discover far more useful information than could an organization, many of which relied on information arising from spontaneous orders, as a business relies of price information.

When Hayek and Polanyi in particular looked more deeply into these issues they realized markets were not the only such process. Prices in the market, degrees of agreement among scientists concerning scientific propositions, votes in democracies, and “hits” in the web constitute similar feedback within different spontaneous orders.

These signals are independent of the concrete details of the interactions generating them. A change in prices does not tell you why they changed, only that they did. Even so by increasing the likelihood those operating within these orders can effectively pursue their own goals they contribute to successful adaptations to systemic changes. All of this takes place without the intervention of a directing hand or hierarchy.

Within any spontaneous order the rules can vary so long as they remain procedural, facilitate cooperation, and treat everyone equally. In markets many possible rules apply to contracts or define private property rights. To use an earlier example, both we the UK, and Norway have healthy markets in land despite significant differences in the contents of the bundle of rights associated with owning land. For the same reasons a democracy can be parliamentary or have a separation of powers and be federal or unitary and still remain a spontaneous order. The rules generating science take somewhat different forms in astronomy and biology but depend on the un-coerced agreement among all scientists as to what constitutes scientific knowledge. Networks of agreement must exist across disciplines such that astronomers and biologists recognize one another as scientists, but neither so recognizes astrologers. In the world wide web different search engines use different algorithms.

Sometimes changes in existing rules are needed because the conditions justifying their original form have changed. The classic example is rules covering pollution, where practices that were once harmless becomes harmful. The contents of bundles of rights need to be redefined. Plurality elections in the American democratic system were devised before political parties existed. For many reasons some (I am one) argue today they should be replaced by majority ones better able to create genuine choices for voters. Some unitary European democracies are becoming more federal. Science is shifting from reliance on printed journals published by corporations with an interest in controlling information to online open source creative commons journals that make it widely available.

Changes such as these need not impair basic feedback processes within these respective orders, but they inevitably alter some of the plans people make within them. For example rules raising the cost of polluting activities will encourage developing new technologies or finding substitutes. Considered abstractly, such changes enable these orders better to facilitate peaceful cooperation and so enrich civil society. Considered most concretely, they facilitate some plans and undermine others.

There is a troubling dimension to this issue. The same feedback making complex projects feasible can also bring them to an end. A business can cease making money, a scientific theory lose its support, a party or politician begins losing elections, and a web site loses hits. If such trends last the organization dependent on resources this feedback provides disappears.

Because changes in rules reconfigures the framework within which discovery processes are pursued, aiding some and injuring others, their details will often be contested even when the need for change is agreed upon.

Organizations stand in relation to spontaneous orders in the same way plants and animals stand in relation to evolutionary and ecological processes. They are made possible by them, and they can come to an end through them. In the natural world plants and animals have two alternatives: they can adapt to any challenges that arise, or they can disappear. But within civil society organizations have an additional alternative: they can change the rules in their favor.

With these observations that apply to all spontaneous orders, I now turn to markets.

Markets

The market is the realm of voluntary contractual exchange of property rights, usually mediated by money prices. This definition covers a wide range of activity, from a child’s lemonade stand to Microsoft, from businesses run as sole proprietorships to corporations with millions of shareholders as well as workers’ cooperatives.

Market exchanges usually begin within civil society, and often remain there. Prices serve as signals enabling decision makers to make better choices in their use of scarce resources. But prices are only signals, and each person can weigh them in relation to others values they hold. Sometimes they will pay more because of these other values. For example, the “buy local” movement seeks to support local businesses and so preserve a more vital community socially as well as economically. “Buying American” seeks to do the same at a national scale. “Buying green” seeks the same outcome with regard to ecological sustainability.

People equating the market with the realm of freedom are thinking of the market in these terms; as a signaling system facilitating cooperation within civil society. But the market can include more than this. It can be capitalistic.

Capitalism

Like civil society, capitalism is more verb than noun. As I use the term it is a process and describes a natural but not inevitable tendency within markets.

Capitalism arises to the degree the market separates itself from full immersion in civil society. As it does relations are reversed and civil society is increasingly subordinated to market processes. Nor is this the end. Ultimately the market itself becomes subordinated to the interests of powerful organizations.

There are three stages in this process.

The first is a natural outgrowth of a market economy. Competition gradually integrates larger and larger regions into a closely knit network of economic exchanges. In the process smaller regions which can be civil societies of their own, increasingly become integrated into larger ones. The growing unification of American states into an ever more comprehensive national market and similar processes taking place in Europe are examples. This process could in principle encompass the globe, and to some degree already has.

As this happens a tension arises in how property rights and rules of contract apply across boundaries. Civil societies define property rights and rules of contract and exchange in keeping with their deeper values. These will vary, as the bundle of property rights does in the US and Norway.

Larger organizations engaged in larger scale enterprises will want to homogenize those different rules whereas smaller scale enterprises specialized in serving their regions seek to preserve the values favored by the bulk of their customers. When different cultures exist these tensions are inevitable. Civil society in California will observe different values than civil society in Italy or Georgia, and yet all these places will have vibrant civil societies.

As the scale of enterprise expands joint stock corporations are organized to raise capital. Their structure privileges those who have invested more capital over those who have invested less. They are organizationally biased to place financial values over all others. Each dollar has equal status, not each individual. This control structure makes it easy to oust managers who do not put profit above all other values. For their CEOs prices are not signals, they are commands. The history of corporate raiders and hostile takeovers illustrates this point.

Especially when there is no concentrated ownership, the value hierarchy of a corporation differs from that of most shareholders. Most individuals will integrate prices with other values in making their choices. Corporations are not humans and operate within a much thinner world value-wise than do human beings because they adapt to the “market ecosystem” not to civil society.

Finally, successful companies often seek to use some of their profits to rewrite the rules in their favor. Often they will succeed. In itself this is not unusual. Main street businesses have long used local governments to their advantage. Today large businesses do the same in Washington, but the change in scale is critical. As members of civil society in many cases people controlling Main Street businesses value more than money, and are involved in day to day interactions with other people in their community. Therefore they influence local politics along a wide variety of values, many of them admirable. Large public corporations care only for monetary income, their leaders rarely interact with people in communities impacted by their privileges, and so corporations use their influence to free themselves from the forces of competition nationally and increasingly internationally. To do so they subordinate civil society’s complex values for the shallow ones reflected in prices.

Today’s rhetoric usually pits business against government, but the reality is quite different. Established businesses in particular benefit from the resources they can bring to bear on political decisions.

• Negotiations for the “Trans Pacific Partnership” are being held in secret, where corporate lobbyists have access but citizens and even members of Congress do not. It turns out there are very good reasons corporations want the details kept secret, and they have nothing to do with free markets or equality under the law.

• Industrial agricultural companies seek to outlaw public reports on the conditions of their animals. Even when acting illegally they use laws they promoted to prevent their exposure.

• Food companies supported bringing the term “organic” under national control, thereby eliminating more demanding standards different states had adopted. Centralization increased their power to further manipulate these regulations in ways opposed by most consumers who wanted to buy organic food.

• Universities are starved of public funds making them increasingly dependent on funds provided by big business and the wealthy, and so subordinated to their interests. In important cases the mission of even the best state universities is being redefined from serving the public and the advance of knowledge to serving corporations.

• Power companies are seeking to use government to destroy the threat of rooftop solar energy. They first tried to use state legislatures to outlaw or hobble rooftop solar energy. When that failed they turned to regulatory agencies to raise the cost of solar even though many studies show that solar actually helps lower the price of energy even for electricity at times of peak demand.

• Disney, inc., played a large role in rewriting copyright law to protect corporations rather than to reward creators.

• Last year companies like Target and others eliminated Thanksgiving as a holiday for their employees last year. Because Thanksgiving focuses on families spending time at home it has never become a profit center like Christmas and increasingly Halloween. Therefore it is subordinated to Christmas sales no matter how great the disruption to families.

• Wage theft is becoming a practice of even very large companies which, when found guilty, still often do not pay the workers they stole from.

• Companies increasingly argue anything a employee learns on the job belongs to them and can be controlled through “non competition” agreements, laying the basis for a new serfdom. For example, a janitor was prevented from taking a better job due to a non-compete agreement.

• Banks that gamble with others’ money keep their winnings and charge taxpayers for their losses are “too big to fail.” Losses are socialized while profits are kept private.

• Prisons are ‘privatized’ with the companies benefiting from incarcerating people lobbying to keep them full.

• Important realms of freedom are eliminated as public places are privatized.

• Corporations not only pay no taxes, they sometimes get millions in “refunds” for the taxes they never paid.

• Private companies use eminent domain laws that destroy the property rights of the weak when they impede their projects. The loudest foes of ‘socialism’ and regulating big business have been almost totally silent when a foreign company seizes private land to build a pipeline to export foreign oil to foreign nations.

Theft, suppression of freedom of speech and of the press, mass incarceration, and the subordination of science to corporate agendas are a few of the impacts of capitalism on a society growing progressively less civil and less free. And on and on in an endless effort to subordinate the complexities of human life as reflected in civil society to market values. This is not government making life hard for business, it is business allying with government to extract profits they could not make in the absence of those privileges.

None of these examples were desired by consumers. None of them serve consumers, let alone people as members of civil society. None resulted from people trying to regulate business against its will. None were denounced as “socialist” by the companies affected. In fact, rhetoric from big business about ‘socialism’ is revealingly absent. Most of these measures victimize people as members of civil society or as consumers, the rest victimize labor or smaller property owners.

Capitalism begins when and to the degree civil society is subordinated to the values of the market, when the signals of prices become commands, and when human beings become resources for ‘the market’ rather than the market being a vital tool for human beings.

But the capitalist transformation does not stop there.

Capitalism vs. the Market

Capitalism ultimately subordinates the market as it has subordinated civil society. Market processes are whittled down so as to serve the largest and most wealthy organizations. They are shielded from its discipline while it remains for smaller businesses. The market exists for smaller enterprises and subsidies and privileges are the norm for the larger, as is explicitly recognized with “too big to fail.” At its core capitalism is the socialization of costs and privatization of gains, and this privatization increasingly concentrates gain at the top.

Capitalism still rests on a market economy, but one removed from subordination to civil society, and then subordinated to large private organizations. The market remains for small scale enterprises, but the large organizations at the top are largely free from market competition because they have used their resources to manipulate the framework of rules to make them so. Prices remain important for organizing production, valuing stock and disciplining management, but competition among the largest businesses is no longer such a worry. They are also remarkably free from the rule of law and on the rare occasions when seriously charged are treated differently than citizens.

In such an environment the largest owners of capital will tend to accumulate more of it. They are freed from much competitive pressure while they have influenced the law in their favor. Consequently civil society is increasingly dominated by a new aristocracy, one Tocqueville perceptively foresaw and diagnosed in the early years of industrial development:

I am of the opinion that the manufacturing aristocracy which is growing up under our eyes, is one of the harshest which ever existed in the world; but at the same time it is one of the most confined and least dangerous. Nevertheless the friends of democracy should keep their eyes anxiously fixed in this direction; for if ever a permanent inequality of conditions and aristocracy again penetrate into the world, it may be predicted that this is the channel by which they will enter.

And as surely as in any authoritarian political system, freedom is slowly strangled. My list of examples above included assaults on freedom of speech, freedom of employment, intellectual freedom, democracy, and equality under the law.

The state and democracy

Modern discussions of public issues consider democracies to be ‘states’. We have monarchies, dictatorships, oligarchies, and democracies, all forms of state. This terminology reflects the same confusion as Hayek identified with the term “economy.” Hayek emphasized the term “economy” is applied to both spontaneous orders and to organizations even though the two are fundamentally different. There is the market economy, but also every business has an economy. In fact the word was first used in the latter sense, as in Aristotle’s discussion of the household economy. Hayek proposed replacing “economy” with “catallaxy” when referring to markets to underline this difference. (1976: 107-132).

The same confusion exists regarding democracy. Historically states arose as organizations of domination where one group controlled another, usually through military conquest. State organizations emerged and developed as means by which those with power could utilize their human and natural resources to better dominate the conquered. Those they controlled were “the people.”

Liberal democracies subordinate the state institutions of police, military, courts, and law making to the systemic principles which characterize Hayekian spontaneous orders The US constitution demonstrates how institutions associated with states became subject to civil society. Traditional state institutions of control are housed in the executive branch: the president, the bureaucracy, along with the police and military power. If this were all there were to the US government we would be a dictatorship or monarchy.

But this is not all there is. Two other branches are independent of the executive, the judiciary and the legislative, and the judiciary itself is also subordinate to the legislature. When push comes to shove Congress can remove any judge or president and no president or judge can over rule congress. In a democracy the “balance of power” is supposed to ensure power ultimately rests in the group most subject to popular control.

This subordination of the executive to the legislature establishes an important difference between democracies and states. Normally a democracy is not a hierarchy. It is an ongoing discovery process where mutually contradictory proposals seek public support, subject to the same rules. In democracies hierarchies appear only in times of crisis, such as war or disaster.

What emerges from the democratic process is a focus on serving the interests of the population as a whole. This is because society is self-governing rather than subordinated to a ruling class. Not surprisingly, relatively democratic nations favor measures that improve the lives of most citizens, such as social security, public education, labor law that evens the playing field between employees and employers, and more accessible medical care. These measures increase and enrich realms of voluntary cooperation in civil society. When capitalism grows in strength these protections are increasingly weakened or abolished, and as we see in the US today, the middle class begins to disappear.

The state reappears

For the same reason a business has interests at cross purposes with a market, political organizations have interests at cross purposes with those of a democracy. Consequently they seek to manipulate the rules in their favor and in the worst cases spread fear that subordinates people’s preferences to the belief their nation is at risk. The result is to create an artificial public will manipulated by those in power.

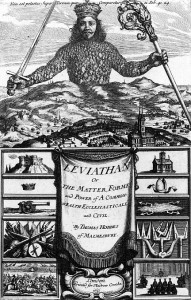

Done long enough and successfully enough a state can arise within what appears on the surface to be a democracy, but more accurately resembles the front piece of Hobbes’ Leviathan: a huge figure of many tiny people with a large crowned head on top.

Alexander Hamilton, whom no one ever accused of being afraid of government, wrote when war is frequent, popular governments must “strengthen the executive arm of government, in doing which their constitutions would acquire a progressive direction towards monarchy. It is of the nature of war to increase the executive at the expense of the legislative authority.” If these conditions were prolonged “we should, in a little time, see established in every part of this country the same engines of despotism which have been the scourge of the old world.”

Permanent war establishes a state on the corpse of democracy. Today we are in incessant conflicts for vague and even inexpressible goals. These conflicts justify increasing surveillance domestically and militarization of the police. In a six month period police in Pasco, Washington, with under 60,000 people, killed more people, including unarmed ones, than did the police in the UK with 64 million citizens in a year. In one month, March, 2015, American police killed more people than UK police have in over 100 years. Those breaking laws at the top, whether they be war crimes or economic crimes, are immune from prosecution. As in the old aristocracies, one set of laws exists for the powerful, another for the people. Like a zombie compared to a human, American ‘democracy’ still retains some of its outward appearances while its inner core is transformed utterly.

Capitalism and the state are not only compatible, within the modern world they attract and support one another. In the US capitalists seek to create government agencies independent of popular control, and even international agencies that could override the people of entire nations in service to capitalism. They provide the largest political support for a defense budget larger than that of the rest of the world combined, a budget never criticized by nearly all concerned with “big government” and “socialism.” A permanent “revolving door” exists between the largest banks and corporations and ‘public service.’

Ideological sleights of hand

Sadly, so-called “market liberals” are usually major allies in this process despite the lip service paid to what they call the ‘free market.’ Consider for example the libertarian critique of ‘the state.’

Politics, libertarians tell us, is “coercion.” ‘The State’ is coercive. The market is voluntary. Therefore we should oppose ‘the State’ and seek to undo any and all regulations on ‘the market.’ In practice the regulations attacked are rarely the regulations capitalists promoted, but rather attempts to keep the market subordinate to civil society. The libertarian Kochs fight more accessible medical care, but are virtually silent in efforts to shrink a bloated military budget. In fact they contribute massively to the party most supportive of growing it. This is the most grotesque hypocrisy, but let’s look at their claims about ‘coercion’.

When we consider a particular vote where we lost, and consider it in isolation, democracy seems coercive. I will argue this is exactly like looking at a game in which one team lost to another and saying the losers were coerced by the winners. Did the winning football team ‘oppress’ the losers by pushing their way into their territory, most certainly without their permission, and scoring? Anyone making such a claim could be accurately described as not understanding football.

In important respects a democracy is like a game in which some will win and some will lose, but all rational players agree on balance ultimately helps everyone. In the case of democracy the ‘game’ is determining what values are best provided for the community as a whole rather than on an individualized basis. As I explained above, this is necessary. Property rights must be defined and modified when very new conditions arise. Contracts need to be enforced. Defense and public safety are valued in every society. The only real issue is who does it.

We play by democratic rules that are ideally fair to all to influence the outcome of the ‘game.’ When the rules are fair complaining that your favored position was not shared by enough to become policy, and so you were coerced, is like complaining you were coerced into losing a ball game because the other team was better than yours.

But one might respond politics is not a game. It is a central part of modern life. We have no choice whereas we have a choice whether or not to play football. True enough, but so is the market. And Hayek uses the exact same reasoning to explain why competition in the market is the best way to coordinate economic activity. (1976, 115-20) Competition is necessary to determine the best baseball team or best soccer team or best scientific theory or best automobile. If we knew the best outcome in advance there would be no need for competition. Competition hardly guarantees the best wins, but the best is more likely to win when all play by the same rules and those rules are fair. The same holds for public policies.

Genuine coercion in democracy happens when rules are unfair to some players. The solution is to improve the rules not end the game. But understanding what needs to be done is impeded by near universal confusions as to the meanings of markets, capitalism, the state, and democracy. Two are compatible with civil society, two are subversive to it. While he never took his analysis quite this far, Hayek’s development of what constitute spontaneous orders gives us the intellectual tools to make sense out of how these terms are related to one another, and so hopefully to preserving the civil society that serves human well-being better than any other form of human association.

There will be two additional parts of this essay appearing at some point: capitalism and labor and capitalism and nature. In both cases capitalism will be shown to be parasitic and ultimately unsustainable. The bottom line to these essays is that viable societies are morally complex as befits the beings that comprise them, and so require an ethical foundation not present in market logic alone. Markets enrich humanity when subordinated to civil society, but when raised above it, as in capitalism, will destroy these same societies.

But this first section alone should demonstrate that those who equate capitalism with the market or the state with democracy, be they on the political right or left, are mixing very different concepts and so ending with very confused analyses.

Bibliography not online.

deTocqueville, Alexis, 1961. Democracy in America, I and II. New Work: Schocken.

Hayek, F. A. 1976. Law, Legislation and Liberty vol. II: The Mirage of Social Justice, Chicago: University of Chicago.

_____, 1973. Law, Legislation and Liberty vol. I: Rules and Order, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1973

_____. 1948. Individualism and Economic Order, Chicago: University pf Chicago,

Mises, Ludwig, 2011. Socialism, An Economic and Sociological Analysis. Ludwig von Mises Institute. http://mises.org/library/socialism-economic-and-sociological-analysis

Polanyi, Michael. 1969. Knowing and Being. Marjorie Grene, ed. Chicago: University of Chicago.

5 thoughts on “Hayekian Insights on Capitalism and Civil Society”